By Joann Lee, LAFLA Special Counsel on Language Justice

With Asian Pacific Islander Heritage Month upon us this May, we commemorate the 150th anniversary of the completion of the transcontinental railroad, largely built by Chinese workers. These workers, who faced extreme racism and exploitative conditions, were excluded from receiving any acknowledgement and very little was documented regarding their contributions. Reflecting on this history, I think about my own experience as a second-generation Korean American, working as a legal aid attorney, and the journey I took to get here.

With Asian Pacific Islander Heritage Month upon us this May, we commemorate the 150th anniversary of the completion of the transcontinental railroad, largely built by Chinese workers. These workers, who faced extreme racism and exploitative conditions, were excluded from receiving any acknowledgement and very little was documented regarding their contributions. Reflecting on this history, I think about my own experience as a second-generation Korean American, working as a legal aid attorney, and the journey I took to get here.

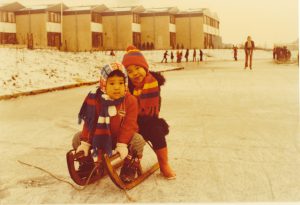

Originally from Korea, my parents came to the United States in the 1960s to pursue graduate studies. My father was born in what is now known as North Korea, during the brutal Japanese occupation of Korea and experienced the Korean War as a young child. When he was 12 years old, he separated from the rest of the family with an older sister, and fled to a small South Korean island where he lived in a refugee camp. He fortunately found another sister on the island but never saw the rest of his family again. My mother was from the South, the second child of seven siblings. A talented pianist, she spent all her waking hours practicing piano at school because she did not have one at home. Both my parents attended college at Seoul National University, but they did not meet until their paths crossed in Riverside, California, and they got married in 1968. My mother postponed her graduate studies to support my father, who was working on his dissertation, and to take care of us. When I was four, my father left academia as a physics professor for a more “regular” job as an engineer at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, and we moved to suburban Maryland, just outside of Washington, DC. My mother was finally able to obtain her graduate degree in music after I started elementary school, balancing her master’s program, working as a piano teacher, and childrearing. In many aspects, I acknowledge that my parents were very fortunate to find work in their professions and training, unlike the Chinese workers and many other immigrants who had no other choice but to take on difficult, dangerous, and exploitive jobs.

Originally from Korea, my parents came to the United States in the 1960s to pursue graduate studies. My father was born in what is now known as North Korea, during the brutal Japanese occupation of Korea and experienced the Korean War as a young child. When he was 12 years old, he separated from the rest of the family with an older sister, and fled to a small South Korean island where he lived in a refugee camp. He fortunately found another sister on the island but never saw the rest of his family again. My mother was from the South, the second child of seven siblings. A talented pianist, she spent all her waking hours practicing piano at school because she did not have one at home. Both my parents attended college at Seoul National University, but they did not meet until their paths crossed in Riverside, California, and they got married in 1968. My mother postponed her graduate studies to support my father, who was working on his dissertation, and to take care of us. When I was four, my father left academia as a physics professor for a more “regular” job as an engineer at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, and we moved to suburban Maryland, just outside of Washington, DC. My mother was finally able to obtain her graduate degree in music after I started elementary school, balancing her master’s program, working as a piano teacher, and childrearing. In many aspects, I acknowledge that my parents were very fortunate to find work in their professions and training, unlike the Chinese workers and many other immigrants who had no other choice but to take on difficult, dangerous, and exploitive jobs.

My upbringing was traditionally Korean American, where I was expected to focus on my studies. There were very few Korean Americans in Maryland at the time, and I grew up lacking a sense of identity and community until I went to Northwestern University, where I got involved in many community issues and student activism. We craved lessons on our own history, like the stories of the Chinese railroad workers, but the university did not offer such classes, and we were forced to teach ourselves. In my senior year, I was part of a campus-wide protest and hunger strike demanding an Asian American studies program (see if you can spot me in the old photo in the link). I fulfilled my parents’ expectations to attend graduate school by choosing the law, in order to do some sort of community-related work. I ended up doing various public interest internships during law school, and like many similarly situated students, I graduated and took the bar without a job.

My upbringing was traditionally Korean American, where I was expected to focus on my studies. There were very few Korean Americans in Maryland at the time, and I grew up lacking a sense of identity and community until I went to Northwestern University, where I got involved in many community issues and student activism. We craved lessons on our own history, like the stories of the Chinese railroad workers, but the university did not offer such classes, and we were forced to teach ourselves. In my senior year, I was part of a campus-wide protest and hunger strike demanding an Asian American studies program (see if you can spot me in the old photo in the link). I fulfilled my parents’ expectations to attend graduate school by choosing the law, in order to do some sort of community-related work. I ended up doing various public interest internships during law school, and like many similarly situated students, I graduated and took the bar without a job.

Shortly after the bar, I was fortunate to get a fellowship at a national Asian American civil rights organization in DC for a year, where I worked on national policy issues “on the Hill.” Policy work created a desire for more direct client and community interaction, so I packed up my bags to relocate to Los Angeles to work at Legal Aid Foundation of Los Angeles. One of the things that drew me to LAFLA was the idea of a specialized project serving Asian and Pacific Islander immigrant communities.

When I joined LAFLA in 2000, I was tasked with conducting outreach to and representing Asian and Pacific Islander (API) immigrants in family law and immigration matters. The Asian and Pacific Islander Community Outreach Project had been created in the 1990s to address the growing needs of the increasing numbers of APIs in Los Angeles County, currently at about 15 percent of the population. With the majority of the API population in Los Angeles County having limited English proficiency, the most critical deterrents to APIs seeking legal services were linguistic and cultural barriers. Having grown up in an immigrant family, I was accustomed to moving linguistically and culturally between two worlds. The task at-hand, however, was far more challenging than I had ever imagined, as I found myself maneuvering into isolated communities that historically have been grossly underserved.

I came to realize that, although we can help navigate the legal system for our clients—that is often not enough. Our clients often face situations that they cannot control and that, even with our advocacy, cannot be fixed. Injustice and systemic barriers are still pervasive, taking the shape of poverty, inequality, discrimination, and racism, which includes the dearth of culturally and linguistically appropriate resources, and the constant vulnerability of government safety nets and programs for the poor, particularly those who are immigrants. This is not to say that our clients have no role to play in accessing justice—many of them will and can overcome these barriers, but others may not. And it is this burden with which we must move forward to not just help our individual clients, but also address the systemic injustices our clients encounter. As I interacted with so many clients who were limited English proficient, I realized that all the systems with which they interacted—the police, the courts, social services, educational institutions, job-training facilities—needed to be accessible.

To address some of these systemic barriers, we decided to tackle the lack of linguistic access in the courts—the one place that our clients should be able to seek justice. When I first started at LAFLA, I did not expect language access to become such an integral part of my practice, but it has continued to be an issue in almost every case I handled. After trying different legal strategies, we decided to file an administrative complaint with the U.S. Department of Justice, which led to a federal investigation of California’s judicial system. This complaint was based on two very brave clients, both Korean-speaking women who were denied interpreters, one for a restraining order request and one for a child custody and support matter. In addition to the extremely hard task of going through the judicial process, they also decided to come forward to voice their demands for language justice in the courts. We now have a language access plan in place for all 58 counties that includes interpreters in all court proceedings and language services for all points of contact outside the courtroom. This is just one example of broader advocacy we have done with our individual clients and their issues.

Through my work, I have realized that language is an important factor in accessing justice, but it is just the entry point of understanding a person’s experiences, background, and culture. Communication is a key tool but sometimes not enough. It does not explain, for example, why a judge may not understand why our immigrant clients are too afraid to call the police. It does not explain why some of our human trafficking survivors could be pulled back into a trafficking situation after obtaining legal status and other benefits. There is a great deal beyond language we have to learn about our clients and their experiences, which will inform our work.

As we continue to push to break down all of these barriers, with one client at a time, one courtroom at a time, or one policy at a time, there are many ways to participate in efforts to expand access to justice. At LAFLA, these issues have always been defined by the clients’ needs. It is my hope that as a legal services community, we will continually seek to understand the complexities of the language and cultural barriers our clients face to ensure justice appropriately and meaningfully for all communities.

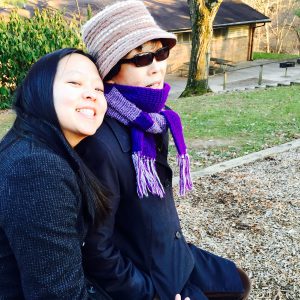

I have been here now for nearly 20 years, working with immigrants who have survived domestic violence, rape, human trafficking, and sexual exploitation. After nine of these years, I had my first child, which greatly changed my perspective of work, life, and everything else. Before having children [pictured right], I put my heart and soul into my work. Through all of it, I never ceased to be amazed by my clients’ resilience through their darkest hours, especially those who had to care for children without any help from friends or family. Some fled from their abusers while pregnant and had to go through childbirth and everything afterward completely alone. I once had a client call me from the hospital because the nurse told her that her son had to have his father’s last name, and she wanted to ask me if that was true. A seemingly small detail—but how overwhelmed she must have felt.

I also began realizing that although work and parenting often tug us in different directions, they can also be very much interwoven. Every day, I still struggle with the balance and intersection of the different spheres in my life. To cope, I have leaned on the strength and resilience of my immigrant clients, who are low-income, survivors of extreme trauma and abuse, working multiple jobs, and raising children on their own. For this, I will be eternally grateful to all my clients.

I wonder how we might have been able to advocate for the Chinese railroad workers today—for better living and working conditions, fair wages, language needs, access to health care, other services for themselves and their families, and basic freedom. Just after the completion of the transcontinental railroad, rising anti-immigrant sentiment, racism, and violence ensued, leading up to the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, which halted immigration, barred all Chinese people from citizenship, and set off decades of racial discrimination and animus against those of Asian descent. Although the diversity within the API community is great, it was the struggle of these decades of racism and injustice that brought our community together collectively to fight for social justice and systemic change. Activists and academics trace the term “Asian American” to the 1960s, when students on college campuses were inspired by the Black Power Movement and Vietnam War protests. It is my hope that our advocacy at LAFLA has made a small contribution to this Asian American Movement.

In 2015, I lost my mother to ovarian cancer, leaving behind my father after 47 years of marriage—another tremendous perspective-changing event in my life. It caused me to reflect even more on how I will teach my kids about what I do, our history, and how to interpret the world. As third-generation Korean Americans, how will they learn and understand the history of those who came before them? I was pleased to see that they were learning about Asian Pacific Islander History Month in school, and my daughter’s fourth grade school curriculum included a lesson on the Chinese railroad workers. Both my son and daughter are in an LAUSD Korean dual language program and growing up confident in their identity as Asian Americans, something I did not experience. I often bring my kids to meetings and legal clinics with me—mostly due to necessity, but also to expose them to my work. Although they may be too young to comprehend now, I am grateful that eventually teaching them about our important work will help shape who they are and what they believe about our society and the world.

In 2015, I lost my mother to ovarian cancer, leaving behind my father after 47 years of marriage—another tremendous perspective-changing event in my life. It caused me to reflect even more on how I will teach my kids about what I do, our history, and how to interpret the world. As third-generation Korean Americans, how will they learn and understand the history of those who came before them? I was pleased to see that they were learning about Asian Pacific Islander History Month in school, and my daughter’s fourth grade school curriculum included a lesson on the Chinese railroad workers. Both my son and daughter are in an LAUSD Korean dual language program and growing up confident in their identity as Asian Americans, something I did not experience. I often bring my kids to meetings and legal clinics with me—mostly due to necessity, but also to expose them to my work. Although they may be too young to comprehend now, I am grateful that eventually teaching them about our important work will help shape who they are and what they believe about our society and the world.